Operations Fortitude South And Fortitude North

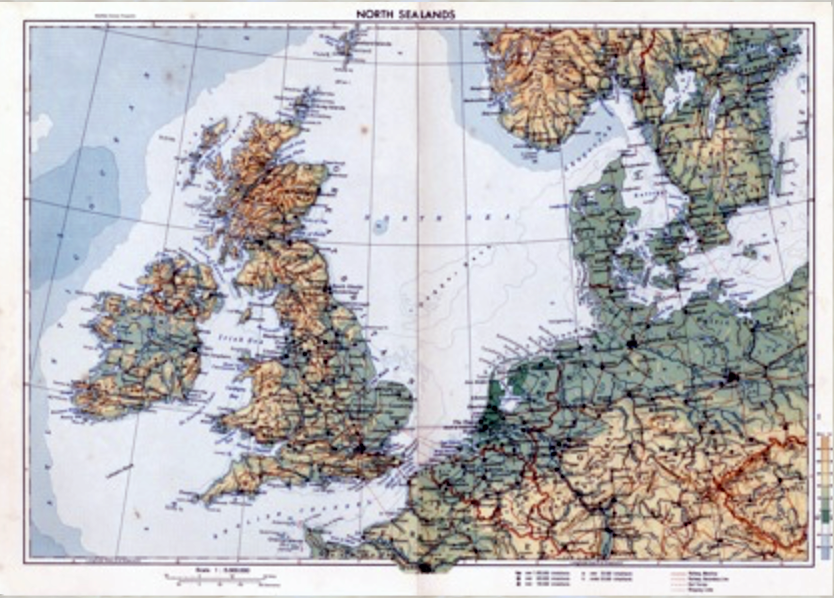

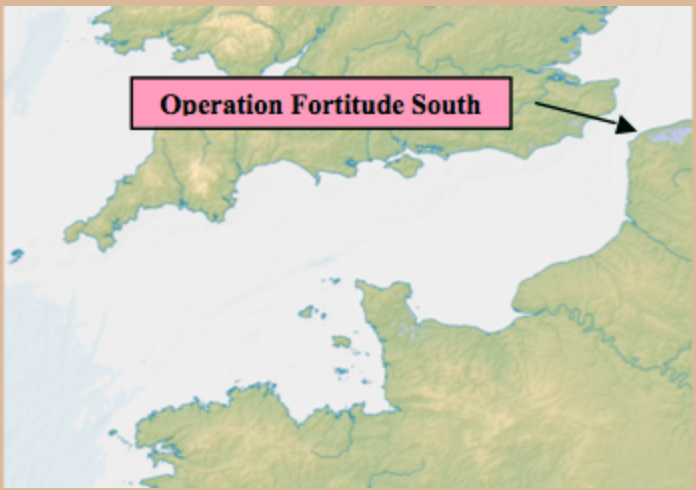

The ultimate success of the Allied landings in Normandy on 6 June 1944, and the subsequent campaign to liberate Europe, were heavily dependant on plans designed to prevent the German High Command from reinforcing its forces in Normandy prior to or after the landings had taken place. All avenues available were employed to persuade Hitler and his generals that the actual landings would take place on the Pas de Calais, the militarily obvious choice, perhaps even in Norway. William Casey has written: “It cannot be stressed enough how much depended on that deception plan. It permeated all Overlord thinking.” (W. Casey, “Secret War Against Hitler, p.100)

The overall Allied deception efforts were organised under Operation Bodyguard of which the two Operations, Fortitude North and its larger cousin Fortitude South, were the main elements.

A complex range of long-term and long-sighted Intelligence efforts was set in train to muddy the waters. These included diplomatic efforts in Sweden (Operations Royal Flush and Graffham) to sow false information which, it was hoped, would leach back to German ears.

Other means involved the RAF which had to exercise great care in its European target selection by avoiding a telling over-concentration of attacks on targets in Normandy itself. A similar restraint had to be placed upon the French Maquis or Resistance groups who couldn’t be seen to be concentrating their acts of sabotage solely on the approaches to Normandy.

While history appeared to be favouring others, General George Patton has to put up with the frustration of apparent action but actual inaction as he was put in charge of an American First Army Group, a wholly fictitious group which existed purely on paper. Patton’s attraction was that he was well known by the Germans. He added ‘clout’ to the deception. Spurious radio traffic, which even involved the BBC sending out sports reports to non-existent troops, was deliberately created to give the impression of a British Fourth Army of 250,000 men gathering and training in Scotland for invasion. Units were sent south then north, back to pre ’invasion’ base areas.

For example, consider the story of Sapper Crompton, 250th Field Company, 42nd Division, Royal Engineers:

“I was a Sapper in the Royal Engineers, 250th Field Company, 42 Division. We were all young, fit men who practiced daily putting Bailey Bridges over rivers for D-Day. One incident in 1944 that made us all wonder why at the time was an order to pack up all our tools & equipment, load the Bailey Bridges onto trucks and head up to Scotland.

We travelled through all the major towns from Kent in the South East through to the Midlands to Yorkshire and on to the North East and arrived late at night in the same day in Edinburgh, Scotland. We were photographed by German aircraft on our way up to Scotland.

We had something to eat, and then during the night fresh drivers drove us as we slept or talked together in the trucks back down the lonely coastal routes and avoiding the towns and build up areas taking all the bridging equipment back to Kent, where we started! We were not observed by any German aircraft on our return journey. We repeated the same journey a few days later, attracting a lot of attention and returned back the same way!

We had no idea why? Only after the war did my son Noel find out that we were all part of ‘Fortitude North’.”

German agents, who had been turned, were used to reach important ears deep in the German intelligence world.

Two agents working for the Germans, John Moe (of mixed Norwegian and British parentage) and Tor Glad (Norwegian born), were landed on the Moray Firth in 1941 with orders to indulge in minor acts of sabotage and intelligence gathering. They had no intention of undertaking such work and immediately handed themselves in to the authorities. They were recruited as Double Agents, feeding false information to their German handlers. Their MI5 handlers used their radios up until early 1944 to send intelligence purporting to show Britain’s interest in landings in Norway: another facet of Fortitude North.

The jigsaw comprised many pieces but, uniquely, the Allies had a means of reviewing how successfully the Germans were assembling them and what picture the Germans believed they were forming. The Allies had Ultra, the ability to decode German secret radio traffic sent via Enigma encoding machines, and could thereby judge the success or failure of their intelligence efforts.

Scotland’s geographical position relative to Norway ensured that it would play host to the operations designed to ensure that German forces based in Norway remained there, prior to and during the period of the landings. In order to achieve this aim, it was decided that German intelligence should be led by all means possible to believe that the Allies were planning to invade Norway from Scotland. This deception operation, named Fortitude North, was co-coordinated from Edinburgh Castle under the direction of Col. RM McLeod. It consisted of a number of different schemes which, put together, would give the impression that a large invasion force was assembling in the Forth area and was training for a Scandinavian campaign. Command of this ‘force’ was given to a well-respected soldier, General Andrew Thorne, and small units of troops were moved into the Forth area to train.

There is some evidence that the creation of visual evidence (invasion shipping, airfields crammed with aircraft, large troop movements, etc.) was attempted but discovered to be less effective than hoped, largely because reconnaissance by German aircraft over the Forth had become a less than dependable means of fooling the Luftwaffe’s photographic interpreters. Put simply, by 1944 the Forth area was too well guarded and was but infrequently visited by Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft.

Other means involved the RAF which had to exercise great care in its European target selection by avoiding a telling over-concentration of attacks on targets in Normandy itself. A similar restraint had to be placed upon the French Maquis or Resistance groups who couldn’t be seen to be concentrating their acts of sabotage solely on the approaches to Normandy.

While history appeared to be favouring others, General George Patton has to put up with the frustration of apparent action but actual inaction as he was put in charge of an American First Army Group, a wholly fictitious group which existed purely on paper. Patton’s attraction was that he was well known by the Germans. He added ‘clout’ to the deception. Spurious radio traffic, which even involved the BBC sending out sports reports to non-existent troops, was deliberately created to give the impression of a British Fourth Army of 250,000 men gathering and training in Scotland for invasion. Units were sent south then north, back to pre ’invasion’ base areas.

For example, consider the story of Sapper Crompton, 250th Field Company, 42nd Division, Royal Engineers:

“I was a Sapper in the Royal Engineers, 250th Field Company, 42 Division. We were all young, fit men who practiced daily putting Bailey Bridges over rivers for D-Day. One incident in 1944 that made us all wonder why at the time was an order to pack up all our tools & equipment, load the Bailey Bridges onto trucks and head up to Scotland.

We travelled through all the major towns from Kent in the South East through to the Midlands to Yorkshire and on to the North East and arrived late at night in the same day in Edinburgh, Scotland. We were photographed by German aircraft on our way up to Scotland.

We had something to eat, and then during the night fresh drivers drove us as we slept or talked together in the trucks back down the lonely coastal routes and avoiding the towns and build up areas taking all the bridging equipment back to Kent, where we started! We were not observed by any German aircraft on our return journey. We repeated the same journey a few days later, attracting a lot of attention and returned back the same way!

We had no idea why? Only after the war did my son Noel find out that we were all part of ‘Fortitude North’.”

Mutt and Jeff

German agents, who had been turned, were used to reach important ears deep in the German intelligence world.

Two agents working for the Germans, John Moe (of mixed Norwegian and British parentage) and Tor Glad (Norwegian born), were landed on the Moray Firth in 1941 with orders to indulge in minor acts of sabotage and intelligence gathering. They had no intention of undertaking such work and immediately handed themselves in to the authorities. They were recruited as Double Agents, feeding false information to their German handlers. Their MI5 handlers used their radios up until early 1944 to send intelligence purporting to show Britain’s interest in landings in Norway: another facet of Fortitude North.

Ultra’s Confirmation

The jigsaw comprised many pieces but, uniquely, the Allies had a means of reviewing how successfully the Germans were assembling them and what picture the Germans believed they were forming. The Allies had Ultra, the ability to decode German secret radio traffic sent via Enigma encoding machines, and could thereby judge the success or failure of their intelligence efforts.

Scotland’s Role

Scotland’s geographical position relative to Norway ensured that it would play host to the operations designed to ensure that German forces based in Norway remained there, prior to and during the period of the landings. In order to achieve this aim, it was decided that German intelligence should be led by all means possible to believe that the Allies were planning to invade Norway from Scotland. This deception operation, named Fortitude North, was co-coordinated from Edinburgh Castle under the direction of Col. RM McLeod. It consisted of a number of different schemes which, put together, would give the impression that a large invasion force was assembling in the Forth area and was training for a Scandinavian campaign. Command of this ‘force’ was given to a well-respected soldier, General Andrew Thorne, and small units of troops were moved into the Forth area to train.

Shipping

There is some evidence that the creation of visual evidence (invasion shipping, airfields crammed with aircraft, large troop movements, etc.) was attempted but discovered to be less effective than hoped, largely because reconnaissance by German aircraft over the Forth had become a less than dependable means of fooling the Luftwaffe’s photographic interpreters. Put simply, by 1944 the Forth area was too well guarded and was but infrequently visited by Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft.

However, the East Lothian area did play host to many of those taking part in the deception schemes. What spare shipping was available was anchored in the Firth of Forth, including in the harbours at Dunbar and North Berwick, with the numbers of vessels in the area rising from twenty-six at the beginning of April 1944, to seventy-one by the middle of May. Jack Tully Jackson described how it looked as though, “…one could have walked with dry feet from MacMerry to Fife.” If German reconnaissance aircraft were able to photograph the ships and barges Luftwaffe photo interpretation experts could only conclude that a large invasion fleet was being assembled.

There are claims that airfields and fields in the Lothians were filled with tent ‘cities’, dummy aircraft, tanks and lorries, all made out of wood and canvas but no evidence has come to light to support this.

There are claims that airfields and fields in the Lothians were filled with tent ‘cities’, dummy aircraft, tanks and lorries, all made out of wood and canvas but no evidence has come to light to support this.

Dummy Tanks - Not used in East Lothian.

Radio Deception – Operation Skye

However, since it could not be guaranteed that German aerial reconnaissance would be able to secure photographic intelligence, more emphasis in Fortitude North was placed on bogus radio signals than on visual deception. The few had to appear to be the many. This operation was code-named Operation Skye. Since the real radio messages of an invasion force could not be sent, small army radio units were used to send out the equivalent volume of signals of a whole army. Parts of this deception were based in East Lothian, the units involved operating around the county and out of Macmerry aerodrome and St Germains.

Troops In Spoof Exercises

The 52nd Mountain Division was involved in an exercise conducted without troops, using radios in vehicles under the control of officers who had orders to maintain normal tactical wireless traffic throughout the period of the exercise. Correct radio procedure was followed and standard coding practice carried out. It was only after the end of the war that the troops involved found out exactly what the purpose of the exercise had been.

Troops Train For Norway

In early 1944 Nos. 2737, 2830 and 2949 Squadrons, Royal Air Force Regiment, were sent to RAF Macmerry. Their training programme included exercises in mountain warfare and the squadrons were issued with equipment for such work – e.g. boots, haversacks and tents. One was issued with snow shoes.

In winter conditions Exercise Snowshoe saw the deployment north to the Cairngorms of some 400 troops, including Norwegian troops and 2830 Squadron, RAF Regiment. There 2830 Squadron was given the task of defending Dalwhinnie Distillery from the attacking Norwegians. The latter had to make the strenuous journey over the mountains on their skis, albeit something they were well used to in civilian life. A mule train, manned by less easily acclimatised Indian troops, was also involved.

Training in the Scottish Highlands for Norwegian conditions.

Troops were also given training in the use of captured German arms. Jack Tully Jackson, a member of 2830 Squadron RAF Regiment, described how he and his unit were taken to a hanger full of captured enemy arms on East Fortune airfield and told they’d better get used to them since where they were going they’d not be easily supplied and would have to live off what they could capture.

Such training, in difficult mountain conditions in the Scottish Highlands and sometimes in severe winter weather, prepared the squadrons for their eventual service in Norway after the Normandy landings had taken place in 1945. However, the presence of the Squadrons in East Lothian and their training in the Highlands was all part and parcel of the obfuscation inherent in Fortitude North.

Such training, in difficult mountain conditions in the Scottish Highlands and sometimes in severe winter weather, prepared the squadrons for their eventual service in Norway after the Normandy landings had taken place in 1945. However, the presence of the Squadrons in East Lothian and their training in the Highlands was all part and parcel of the obfuscation inherent in Fortitude North.

Captain Joe Brown Recalls Operation Fortitude North

Captain Joe Brown, 7th/9th Royal Scots.

My grateful thanks to Major Joe Brown for the following comprehensive account of the varying elements involved in Operation Fortitude North. It was written by Captain (later Major) Brown:

“I played a part in Fortitude North. The 52nd (Lowland) Division under the guidance of Norwegian officers and NCOs underwent intensive training in high altitude warfare in the Scottish Highlands. As a young officer with the 7th/9th Royal Scots my Battalion trained to manoeuvre and fight in hilly and mountainous terrain. We all did ski training and a selected group was earmarked to form a fast-moving strike force. Infantrymen tackled rock climbing and [how] to survive in ice and snow conditions whilst using mules for our heavy equipment. It hardened us and made us proficient to the extent that we did not question the belief that we were a Mountain Division destined for Norway.

It was known that the Germans in Norway were taking an active interest in what we were doing. We knew they could intercept our radio signals during training and our unwitting occasional breaches of radio discipline provided them with varying intelligence that we were being trained to liberate Norway. They not only listened to conversations but could, through surveillance techniques, detect our locations and track our movements. Directional finding systems using a searching antenna, could tune into a radio station and when it had obtained its best signal strength [it was] claimed they could pin-point the transmitter’s location with accuracy to less than one degree [of error].

“I played a part in Fortitude North. The 52nd (Lowland) Division under the guidance of Norwegian officers and NCOs underwent intensive training in high altitude warfare in the Scottish Highlands. As a young officer with the 7th/9th Royal Scots my Battalion trained to manoeuvre and fight in hilly and mountainous terrain. We all did ski training and a selected group was earmarked to form a fast-moving strike force. Infantrymen tackled rock climbing and [how] to survive in ice and snow conditions whilst using mules for our heavy equipment. It hardened us and made us proficient to the extent that we did not question the belief that we were a Mountain Division destined for Norway.

It was known that the Germans in Norway were taking an active interest in what we were doing. We knew they could intercept our radio signals during training and our unwitting occasional breaches of radio discipline provided them with varying intelligence that we were being trained to liberate Norway. They not only listened to conversations but could, through surveillance techniques, detect our locations and track our movements. Directional finding systems using a searching antenna, could tune into a radio station and when it had obtained its best signal strength [it was] claimed they could pin-point the transmitter’s location with accuracy to less than one degree [of error].

Having established a Mountain Division capable of fighting in Norway was actively training in Scotland, the operation used these well-established enemy systems of listening and location detection to deceive them into thinking that the Division was moving from the Scottish Highlands south towards the Tay and Forth Estuaries to ports that could be used for embarkation to Norway. 52 (Scottish) Division headquarters organised a structured signals exercise and provided the various infantry battalions (and support troops?) with 19 Wireless Sets operated by Royal Signals – usually used for communication between Brigade Headquarters and Battalions and from Brigades to Division - each battalion having to man a number of these 19WS with two officers. I was one of them and along with a major we accompanied the WS19 signals truck and 15-cwt. admin vehicle and set off to fulfil a programme of orchestrated signals traffic as we travelled south.

Our various stops during the exercise were planned as were the principal signal messages to be sent, these being interspersed with spontaneous radio traffic in response to routine messages that were also transmitted. I undertook to respond on the 19WS to transmissions normally dealt with by a staff officer and the major would come to the set when Sunray (commander) was called. All of us in the Battalion and those taking part were completely unaware [as to]why the exercise was being carried out, except – and this was most unusual - that it was being directed by Divisional Headquarters. We did not learn of its intent until after the War.

Amongst Hitler’s many intuitions was his belief ‘Norway would be a sphere of destiny’. Certainly no troops were removed from Norway to reinforce the Russian front, and this may indicate the existing force was considered the minimum necessary to hold the country, which by its nature had isolated major centres making it difficult to manoeuvre reserves to meet contingencies in its defence. [History of Cossac, Merriam Press (USA) (2008) pp 34-35 refers.] However, it is to be noted that even six weeks after Normandy some 150,000 German troops were still in Norway.

I would argue that the real intent and value of the well conceived and executed Fortitude South and North was the sense of bewilderment that it created; the German High Command having to cope with Normandy and the seemingly imminent landings in the Pas de Calais and Norway. I believe we were in the market to buy uncertainty, indecision and hesitation, knowing that any delay in the commitment of reserves would be of the utmost value during the vulnerable days of fighting to secure and consolidate our bridgehead in Normandy.” 2

Several historians have criticised the value of Fortitude North, claiming that it was ineffective and failed to convince the Germans to send reinforcements to Norway. Attention and credit have tended to focus upon its larger and more undeniably successful southern cousin. However, they have yet to explain why the German garrison in Norway was raised, some sources maintaining to around 372,000 men by early 1944, other sources claiming a figure of 250,000. Greater note also needs to be taken of the fact that no German reinforcements were sent from Norway to Normandy in time to stop the landings or delay the Allied advance into France, despite there being significant forces in Norway which were surplus to the requirement to defend Norway itself from invasion.

The arrival of such units in the early days of the landings would have done much to crucially tip the balance against the Allies. The role of Operation Fortitude North therefore deserves more generous attention from historians and a more even assessment of its importance is required. While East Lothian cannot lay claim to having been the ‘home’ of the deception plan’s main elements, work carried out here by the Royal Signals and by the RAF Regiment among others, do allow it to lay claim to having played a not insignificant role in helping to protect the Allies on D-Day from the attention of significantly larger German units.

Ultimately the question remains unanswered and perhaps unanswerable: to what extent were Hitler and the High Command deceived by the full range of Allied deception plans? There’s no doubt that Hitler hesitated to commit German forces (especially heavy tank units) at crucial moments during the landings. The strange logic behind the retention of such a large German garrison in Norway has yet to be satisfactorily explained and it is not unrealistic to suggest that this logic and hesitation had their roots in the wealth of persuasive but spurious intelligence German groups had gathered, courtesy of Operation Bodyguard and its components Fortitude North and Fortitude South.

1. WW2 People's War is an online archive of wartime memories contributed by members of the public and gathered by the BBC. The archive can be found at bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar

2. Joe Brown www.ww2talk.com

Our various stops during the exercise were planned as were the principal signal messages to be sent, these being interspersed with spontaneous radio traffic in response to routine messages that were also transmitted. I undertook to respond on the 19WS to transmissions normally dealt with by a staff officer and the major would come to the set when Sunray (commander) was called. All of us in the Battalion and those taking part were completely unaware [as to]why the exercise was being carried out, except – and this was most unusual - that it was being directed by Divisional Headquarters. We did not learn of its intent until after the War.

Amongst Hitler’s many intuitions was his belief ‘Norway would be a sphere of destiny’. Certainly no troops were removed from Norway to reinforce the Russian front, and this may indicate the existing force was considered the minimum necessary to hold the country, which by its nature had isolated major centres making it difficult to manoeuvre reserves to meet contingencies in its defence. [History of Cossac, Merriam Press (USA) (2008) pp 34-35 refers.] However, it is to be noted that even six weeks after Normandy some 150,000 German troops were still in Norway.

I would argue that the real intent and value of the well conceived and executed Fortitude South and North was the sense of bewilderment that it created; the German High Command having to cope with Normandy and the seemingly imminent landings in the Pas de Calais and Norway. I believe we were in the market to buy uncertainty, indecision and hesitation, knowing that any delay in the commitment of reserves would be of the utmost value during the vulnerable days of fighting to secure and consolidate our bridgehead in Normandy.” 2

Fortitude North - A Success Or Not?

Several historians have criticised the value of Fortitude North, claiming that it was ineffective and failed to convince the Germans to send reinforcements to Norway. Attention and credit have tended to focus upon its larger and more undeniably successful southern cousin. However, they have yet to explain why the German garrison in Norway was raised, some sources maintaining to around 372,000 men by early 1944, other sources claiming a figure of 250,000. Greater note also needs to be taken of the fact that no German reinforcements were sent from Norway to Normandy in time to stop the landings or delay the Allied advance into France, despite there being significant forces in Norway which were surplus to the requirement to defend Norway itself from invasion.

The arrival of such units in the early days of the landings would have done much to crucially tip the balance against the Allies. The role of Operation Fortitude North therefore deserves more generous attention from historians and a more even assessment of its importance is required. While East Lothian cannot lay claim to having been the ‘home’ of the deception plan’s main elements, work carried out here by the Royal Signals and by the RAF Regiment among others, do allow it to lay claim to having played a not insignificant role in helping to protect the Allies on D-Day from the attention of significantly larger German units.

Was Hitler Fooled?

Ultimately the question remains unanswered and perhaps unanswerable: to what extent were Hitler and the High Command deceived by the full range of Allied deception plans? There’s no doubt that Hitler hesitated to commit German forces (especially heavy tank units) at crucial moments during the landings. The strange logic behind the retention of such a large German garrison in Norway has yet to be satisfactorily explained and it is not unrealistic to suggest that this logic and hesitation had their roots in the wealth of persuasive but spurious intelligence German groups had gathered, courtesy of Operation Bodyguard and its components Fortitude North and Fortitude South.

1. WW2 People's War is an online archive of wartime memories contributed by members of the public and gathered by the BBC. The archive can be found at bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar

2. Joe Brown www.ww2talk.com